[Various editions of Sir Philip Sidney's poetry and prose, annotated by William A. Ringler Jr., editor of the landmark Poems of Sir Philip Sidney (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1962), including:

The Complete Poems of Sir Philip Sidney, ed. Alexander B. Grosart (London, 1877)

Astrophel and Stella, ed. A.W. Pollard (London, 1888)

The Last Part of the Countesse of Pembrokes Arcadia, Astrophel & Stella and other Poems, The Lady of May, ed. Albert Feuillerat (Cambridge, 1922)

Astrophel and Stella, ed. Mona Wilson (London, 1931)

Astrophel et Stella, ed. Michel Poirier (Paris, 1957)

Not all of our rare books are all that old. Our interesting collection of books annotated by twentieth-century Renaissance scholars—including those donated by Samuel Schoenbaum and the historian J.H. Hexter—are absolutely unique, one-of-a-kind items, many of which reveal the genesis of important scholarly work; for example (and I will probably blog about this one day), we own Samuel Schoenbaum's copiously annotated copy of Alfred Harbage's Annals of English Drama, a book updated by Schoenbaum in a revised edition of 1966.

In today's entry I discuss our most important collection of books annotated by a famous scholar, the editions of Sir Philip Sidney's poetry formerly owned by William A. Ringler, Jr. These books are important not only because the extensive annotations help us understand how Ringler thought and worked, but also because he used these books to prepare and establish the texts of Sidney's poetry for his 1962 edition. For the rest of this entry I will investigate the case of Sidney's famous sonnet sequence Astrophel and Stella, with an eye towards understanding how Ringler used book-annotation to prepare his edition.

According to his textual notes on Astrophel and Stella in the Clarendon Poems (457), Ringler checked six different modern editions in the process of preparing his new text: Grosart (1873), Pollard (1888), Flügel (1889), Feuillerat (1922), Wilson (1930) and Poirier (1957). We own Ringler's annotated copies of all these books save the Flügel. The books contain a range of manuscript annotations, almost all of which are directly related to the textual history of Astrophel and Stella. For some of these Ringler used a system of color-coded annotations (referenced in the image above) to record variant readings in different textual witnesses. The abbreviations seen in these books ("13" "98") are the same he uses in the Poems.

|

| Title Page to Grosart's edition (1877) |

|

| Upper cover, Pollard's edition (1888) |

|

| Title Page, Pollard's edition (1888) |

|

| Title page, Feuillerat's edition (1922) |

|

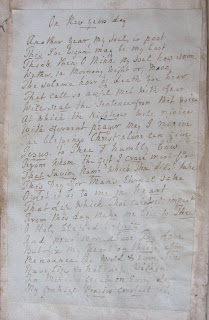

| MS notes from Ringler's copy of Feuillerat |

If Pollard prepared the best text of the "earlier editions," Albert Feuillerat may have produced the worst. Apparently Feuillerat followed his immediate predecessor (Flügel 1889) in making very poor editorial decisions. Ringler summarizes the situation: "Flügel provided an unhappily inaccurate reprint of Q1, which he wrongly assumed represented the earliest state of Sidney's text...In 1922 Feuillerat, unfortunately following Flügel's mistaken notion of the textual relationships, printed a diplomatic transcript of Q1 with appended variant readings from Bt, Q2, 98, and all subsequent folios, but he provided no analysis of the significance of his variants" (457).

As one can see from the images, Ringler's copy of Feuillerat is the most copiously annotated book from his collection of Astrophel and Stella editions. According to the manuscript note above (last image; taken from page facing the beginning of Astrophel and Stella), "Feuillerat's text is from the Newman quarto (1591) [Q1], the worst possible text of A+S—best basis is 1598 quarto" (I think he means the 1598 folio here, but he could refer to Q3 of A & S, printed [1597-1600]). It is interesting to compare the content and tenor of this MS note to the section quoted above from the 1962 Poems (both of which serve similar evaluative functions); words like "unhappily" and "unfortunately" come off slightly less harsh than the MS "worst possible text."

According to Ringler's color-coded key, the annotations record corrections from Q1 (Feuillerat's copy-text), and variants from Q2, Q3, and "Bt," or, the "Bright Manuscript" (British Library MS Add. 15232). Ringler clearly used his copy of Feuillerat's edition to death, considering the poor state of the binding (see below).

Mona Wilson's 1930 edition is "based on 98, with 53 emendations from Q1 and Q2" (Ringler 457). Although she wrote a "useful" introduction, Ringler doesn't approve of her "eclectic" method, "her text [being] less close to Sidney's original than Pollard's" (ibid).

This time without using his typical color-coded system, Ringler notes a number of textual variants in his manuscript marginalia.

Finally, our least annotated but perhaps most personal of Ringler's Astrophel and Stella copies is the French edition prepared in 1957 by Michel Poirier, whose gift inscription to Ringler appears on the half-title.

"To Professor William A. Ringler, with all my best wishes for the completion of his own edition of Sidney's poems. Michel Poirier. December 1957"—a pleasant sentiment, from one Sidney editor to another.

The intellectual labor Ringler invested into these manuscript notes translated directly into his most enduring scholarly work, the monumental Poems of Sir Philip Sidney. This edition offers an admirable model for any serious editor, and to this day—nearly fifty years after its publication—it remains the standard text of Sidney's poems.