Imprinted at London: By Thomas East, 1581

[44], 688, 699-1194 p. ; 19cm. (4to). Plain sheep binding

Our collection's only example of a printed commonplace book in English, this copy of Merbecke's Scriptural handbook is in fairly poor condition, as it clearly has been well used over time. Fortunately a dense layering of ownership inscriptions has survived on the book's opening leaves, documenting two centuries of male and female owners in the British Isles.

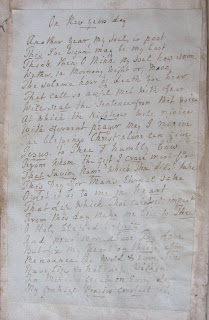

The first inscription (in pencil), reads "W. Blacks Book Kelsocleugh [???] 9 1805 [?]" (Kelsocleugh or Kelso is in the Scottish Borders, Scotland.) In the next couple of leaves W. Black inscribes a prayer taken from Edward Young's verse "Paraphrase on part of the Book of Job," from The complaint: or, night-thoughts on life, death, and immortality. To which is added, a paraphrase on part of the Book of Job (first pub with the paraphrase in 1750; reprinted numerous times throughout second half of eighteenth century). Black has excerpted the paraphrase of Job 42, the book's final chapter.

It reads:

William Black his Book

Kelsocleugh may the 7 180[*]

William Black Kelsocleug[h]

thou Canst accomplish all things lord of might

and evry thought is naked to thy Sight

But oh thy ways are wonderful and lie

Beyound the deepest reach of mortal eye

oft have I heard of thine almighty power

But never saw thee till this dreadful hou[r]

Oerwhelmed with shame the lord of life I see

abhor myself and give my soul to thee

Nor shall my weakness tempt thine anger mo[re?]

man was not made to question but adore

Job 42 1--7

on lifes fair tree fast by ^the^throne of god

what golden joys ambrosial Clustring glow

[second section]

O thou who dost permit these ills to fall

for gracious ends and would that man should mourn

O thou whose hands this goodly fabric framd

who knowst it best and wouldst that man should know

what is this sublunary world a vapour

a vapour all it holds itself a vapour

earths days are numberd or remote her doom

as mortall tho less transient than her sons

yet they doat on her as the world and they

were both eternal Solid thou [a dream]

young

[in pencil] O thou [???? this penciled note is difficult to read]

E. Simpson Alnmouth

Jany 5th 1850

William Black transcribed the first part (before "Job 42 1--7") from the concluding lines of Young's "Paraphrase." He extracted the two lines at the bottom of the first page from "Night the First" of Night Thoughts. On the second leaf he wrote down a passage from the eighth night of the same poem. From this passage he omitted three lines between the last "vapour" and "earths days"; they read:

From the damp bed of Chaos, as they beam

Exhaled, ordained to swim its destined hour

In ambient air, then melt and disappear.

Black attributes the poem to "young" in the final line. The penciled inscription is in the same hand as William Black's 1805 [?] pencil signature (see above). An additional inscription in ink—"E. Simpson Alnmouth Jany 5th 1850"—documents the book's latest nineteenth-century owner. And as you probably noticed, the verso of the leaf with Black's transcription of Young's "Paraphrase" bears the inscription "W. Leydon."

The next two openings offer rich provenance information, recording numerous owners and dates while also preserving a notice of an early rebinding.

These two pages contain the following items in manuscript:

1) sums in an eighteenth century hand

2) inscriptions of a Robert Jobson, one dated 1763

3) inscriptions of William Black, dated 1797

4) inscriptions of Thomas Leydon, dated 1794, Denholm [also in Scottish Borders]. Probably related to the "W. Leydon" mentioned above.

5) pen trials in numerous hands

6) this note: "this Book was printed in the year 1581 Binded 1802 at verry great age"

Here is a similar list for the next opening (see below):

1) several inscriptions of Robert Jobson, one dated 1772

2) inscription of Mary Dent, Gateshead June 31th [sic] 1704

3) inscription of John Thomson, dated 1707

4) inscription of William Black, dated 1798

Most of these inscriptions, with the exception of Mary Dent's, have Scottish provenance. The note about the binding in 1802 (on the first leaf) is very interesting, capturing an owner's care for a treasured book "at verry great age." Here is a picture of the plainly bound sheepskin binding:

Sheepskin is softer but less durable than calf or goatskin, and for this reason few sheepskin bindings from the early modern period survive without a few tears or imperfections. Sheepskin was the cheap alternative to calf; the finest bindings were made from goat.

None of the book's five former owners annotated the printed text of Merbecke's A booke of notes and common places, although the work remains interesting in its own right. Here are several sample images of the text which amply demonstrate the book's content and style:

One leaf bears a final ownership inscription, belonging to Thomas Leydon:

I haven't attempted to track down the identities of the book's former owners, although I am sure the answers lie in Google Books searching nineteenth-century English genealogical works. All in all a book with great manuscript content. This is one of two books we own with extensive Scottish provenance; the other is a copy of Sidney's Arcadia that I plan to write about at some point this summer.