|

| the Garden of Eden, from The Holy Bible [Bishop's Bible] (1602) |

Early printed Bibles frequently contain woodcut images of Eden, as seen above in the image from the 1602 Bishop's Bible. Our quarto copy of the KJV features a similar image.

|

| Engraved illustration in Paradise Lost (London: Tonson, 1705): Book Nine |

|

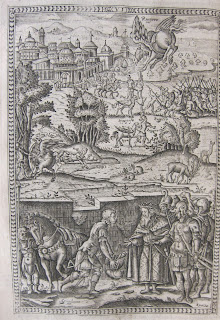

| Engraved illustration in Ariosto's Orlando Furioso, trans. John Harington (1591): Canto Six |

Ariosto’s poem had an enormous influence on Edmund Spenser’s Faerie Queene (1590), whose allegorical knight Guyon encounters the “Bower of Bliss” in Book Two. In the last canto Guyon enters the bower, “a place pickt out by choice of best alive, / That natures worke by art can imitate: / In which what ever in this worldly state / Is sweet, and pleasing unto living sense … Was poured forth with plentifull dispence, / And made there to abound with lavish affluence.” Despite its profound beauty, the Bower of Bliss is a site of temptation and evil in the allegorical project of the poem, and so must be destroyed. In an unsettling show of violent power that to this day troubles critics, Guyon brutally razes the bower to the ground, spoiling its “plentifull dispence” and “lavish affluence”:

But all those pleasant bowres and Pallace braue,

Guyon broke downe, with rigour pittilesse;

Ne ought their goodly workmanship might saue

Them from the tempest of his wrathfulnesse,

But that their blisse he turn'd to balefulnesse:

Their groues he feld, their gardins did deface,

Their arbers spoyle, their Cabinets suppresse,

Their banket houses burne, their buildings race,

And of the fairest late, now made the fowlest place.

|

| "May," from John Evelyn, Kalendarium hortense (1683) |

|

| Sir Thomas Browne, The Garden of Cyrus (1658) |

|

| a Quincuncial Pattern |

Intended as a “Garden Discourse” rather than a “massy Herball” (like John Gerard’s Herball—also owned by the Center), the work begins with a discussion of Babylon’s hanging gardens and the quincuncial layout of King Cyrus’ garden at Sardis. As the author notes in the dedicatory epistle to Nicholas Bacon, The Garden of Cyrus "range[s] into extraneous things, and many parts of Art and Nature...follow[ing] herein the example of old and new Plantations, wherein noble spirits contented not themselves with Trees, but by the attendance of Aviaries, Fish Ponds, and all variety of Animals, they made their gardens the Epitome of the earth, and some resemblance of the secular shows of old."

Browne proceeds to trace the “X” or “net-work” (i.e. shaped like a net) pattern in the world around him, noting architectural styles, manners of sitting cross-legged, reticulated windows, the “pyramidal” cuts on precious gems, staggered battle lines, and astral constellations. His account of terrestrial and submarine plant life finds the quincunx in pineapples, seed pods, leaf structures, and various flowers. He finds it in the animal world, marking the scales of rattlesnakes and fish, the bee’s honeycomb, and even human skin. He points out that the motion of fins, wings, and human limbs depend on a back-and-forth, X-shaped movement. He even likens the elliptical shape of sound and light waves to the “decussated” line of the quincunx. At the end of his treatise, Browne applies the quincuncial form to more abstract ideas, including “intellectual reception” (“intellectual … lines be not thus rightly disposed, but magnified, diminished, distorted, and ill placed … whereby they [people] have irregular apprehensions of things”) and mystical philosophy. The structure of a garden, as Browne so creatively implies, can indeed reflect the organizational principles of nature itself, and become an “Epitome of the world.”